IV. The lives and oeuvres of eight major literati painters of the Yuan, Ming and Ch’ing dynasties

[A note on names: Since most Chinese readers can recognize names alphabetically transcribed, it serves no purpose here to include the Chinese characters for such names, which would have to be given in traditional and simplified forms to satisfy two audiences. Likewise, since those who know the pinyin system for reproducing names can recognize them in Wade-Giles (used in traditional art historical scholarship), and vice versa, only the latter forms will be used.]

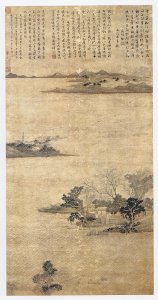

Chinese landscape painting, like everything in China, has a long history. Unfortunately but few examples of works by the earliest figures of great reputation have survived, at least in their original versions. Though the monumental representation of mountainous landscape forms begins toward the end of the T’ang, such paintings need not occupy us here. However, so famous are certain figures belonging to the period between the T’ang and the Northern Sung, the period that includes the Five Dynasties and the Ten Kingdoms, that we need at least to know their names, if not to view what are often copies of their works or works long misattributed to them. Readers curious about these antecedent painters’ works may Google their names

It is the landscape types that are important, along with the lore of schools and influences, of genealogical affiliations, of early theories (propounded often by the painters themselves, though, again, some utterances and anecdotes that surround their work may be apocryphal). Chinese criticism views painting in relation to the painter, or to a moral legend about him. The dates of many painters are uncertain, the dates of undated paintings even less reliable. Instead of putting these early painters, then, in strict chronological order, I will take them up instead in the order of the importance that later painters assigned to them. We begin with a tetrarchy of figures from the Five Dynasties period: Tung Yuan, Chu Ran, Ching Hao and Kuan Tung.

Tung Yuan (ca. 900-962) came from a place that corresponds in name to the modern Nanking, which in the 10th century was a center of culture and art. Not well known in his day, he gained a reputation in the Yuan Dynasty, when he became an object of imitation. He was known from many paintings, which enabled different painters to imitate different aspects of his work. Tung Yuan’s elegant style became in retrospect the standard for nine centuries of painting. He and his famous pupil, Chu Ran, founded the southern school of landscape painters and with Ching Hao and Kuan Tung, of the northern school, were the most seminal artists. Given to sophisticated perspective, Tung was also known for his advanced brush technique.

Chu Ran, a Buddhist monk also from Nanking, was a famous decorator, whose murals have not survived. Nor do his scrolls have reliable attributions. He is associated with a landscape type that grows out of Tung Yuan’s rounded contours and soft brushstrokes, but he shows no sign of the older painter’s horizontal, level-distance landscape format. Unlike the varied oeuvre of his master, Chu Ran’s production is relatively uniform (again, if attributions are credible). Despite a spiritual Buddhist moniker, Chu Ran (his family name now unknown) moved in the circle of the Southern T’ang court and moved with the court around 975, when Li Hou-chu, surrendered to the Northern Sung dynasty and shifted the court to (modern) Kaifeng.

Ching Hao is paired with the today less well known figure Kuan Tung. In their day they constituted the Ching-Kuan school, just as Tung Yuan and Chu Ran constituted the Tung-Chu school. Ching Hao (fl. 910-940) deserves more of our attention, for he was a major, if modestly spoken, theorist. Ching compiled a list of six attributes of serious painting that replaced an earlier dogma of six other attributes. He fled the disturbances at the end of the T’ang Dynasty to establish himself in retreat in the T’ai-Hang Mountains of Southern Shansi, where he wrote a treatise on painting, the “Pa-Fa-Chi” (literally notes on brushwork). Ching felt that the ultimate criterion of painting was Truth, important for later literati painters of integrity.

He elaborates six essentials of painting: Ch’i (spirit, life breath, vitality), Yun (harmony, rhythm), Ssu (thought or mental concentration, a hallmark of literati painting that proves to be an important analogy between Kant’s “ideas” and the “ideas” of the literati masters), Ching (scenery or motif), Pi (the brush, or physical brushwork, related to Kant’s “sensitivity”) and Mo (literally the painter’s ink, but by extension the tonality of evocative painting and its subjectivity, again reminiscent of Kant). Ching’s theory, like Kant’s theory of perception in the West, is a turning point in the development here of the early Chinese theory of painting. In practice, however, Ching Hao preferred to the vague wash the chiseled “axe strokes” of the T’ang.

His own relatively severe work, to modern eyes a little redundant and artificial, became the foundation for the 10th century masters, in particular for Kuan Tung and Fan Kuan, one of whose most famous paintings stands at the head of this section. Technically, Ching Hao was responsible for a most important innovation, the so called ts’un-fa, a sharp brushstroke felt to be suitable to the representation of hard, stony surfaces, such as characterize northern landscapes and Northern Sung landscape painting. Fan Kuan studied Ching Hao and, despite controversial dates, may be regarded as his disciple. Li Ch’eng also studied Ching Hao. As well as for the ts’un-fa Ching Hao was famous for developing the technique yung-mo, or ink washes.

Chinese criticism relies upon mnemonic tags, often loosely associated with a school or specific geography. It is a poetic rather than analytic theory. Ching Hao felt, for example, that ts’un-fa was a way for “the heart to follow after the brush,” thereby promoting a spontaneity that might seem at odds with his disciplined work. “The image is to be seized without hesitation,” he wrote, “so that the representation does not suffer.” Chinese criticism is less theoretical than practical, part of the painter’s praxis. “If the ink,” said Ching, “is too rich, it loses its expressive quality; if too weak in tone, it fails to achieve a proper vigor.” Despite his influence on Northern theory, almost none of Ching Hao’s own works have survived to the present.

Li Ch’eng is another early influential figure, more sympathetic to modern eyes (though few of his paintings survive). He was regarded as foremost among the mid-10th c. landscapists. His works, like those of Ching Hao, would have been important as long as they did survive, and perhaps continued to be influential in copies. To his contemporaries Li’s work seemed like a more direct manifestation of nature than had been encountered before. “The phenomena came spontaneously out of him,” one of them said in awe. According to Max Loehr (to whom I am heavily indebted, along with Osvald Sirén and James Cahill), “Li Ch’eng studied Kuan Tung.” “Wen Cheng-Ming,” he says, “recognizes in Li Ch’eng two traditions.”

These were codified as originating with (1) the almost mythical figure of Wang Wei, a T’ang dynasty poet and painter, again, of whose oeuvre few, if any, paintings remain, but who was routinely credited with inventing the “brush line,” and (2) Kuan Tung, who was known for his “textures and tints.” The tradition here is contrasting the hard and the soft of things, carrying forward legend more than actual tradition. No sooner has Loehr (following as always Chinese sources in his information and generalizations) mentioned Wang and Kuan as Li Ch’eng’s two most abiding influences, does he mention Ching Hao. The talk of painters and influences on them, in Chinese critical tradition, is often a matter of add-ons and afterthoughts.

It is also a matter of politics. Shortly we will turn to one of Fan Kuan’s greatest paintings, Travelers among Streams and Mountains, placing it in relation to Kuo Hsi’s Early Spring and Li T’ang’s Whispering Pines in the Gorges (all three appear above). The famous Sung poet, Su Tung-p’o, a painter of sorts himself, said that he found Fan Kuan’s realism slightly disturbing. Here the tradition is contrasting the realistic and the vague. Early on Fan Kuan was said to have depended upon Ching Hao’s example, later on upon Li Ch’eng’s. But a third influence was said to be that of Mi Fei, whose work in no way resembles Fan’s

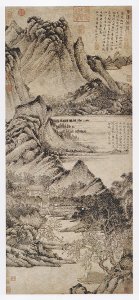

I now encourage the reader to click on the first image above and spend some time examining Fan Kuan’s fundamentally Confucian Travelers. About the year 1000 Fan, a native of Shensi, was the uncontested master of landscape. Unlike the vague prospects that we encounter in the Five Dynasty masters, his forms relentlessly present the landscape as in the foreground. No scholar, no writer, Fan Kuan knew his subject matter at first hand, often sequestering himself in the mountains of the Ts’ing-ling range for a month at a time. We note in Travelers among Streams and Mountains the mass of a single mountain, whose centrality may be thought of as corresponding to the Confucian moral concept Chung Yung, The Mean.

Loehr characterizes Fan’s manner as “antique severity approaching indifference and urbanity.” Human figures inhabit the scene, but so unobtrusively as almost to go unremarked. We can make out a caravan moving along the river bed, a solitary peasant higher up, burdened with pole and baskets. It is not a painting that requires great analysis, though study reveals a remarkably appropriate variety of brushstrokes employed. Fan Kuan himself said, “Rather than learning from other men, I should also learn from the things themselves, or better still, from their inner natures.” Loehr speaks of him as interested in noumenal presence. We will have future reference to this great work of Fan Kuan’s as a fundamental Northern Sung type.

Kuo Hsi is the Taoist counterpart to the Confucian Fan Kuan. I encourage the reader to click on the second image, of Early Spring, and consider some of its details first by way of this enlargement of the digital photo. Whereas Fan Kuan is, in his contemporaries’ conception, “massive and substantial,” Kuo Hsi is everywhere in flux, though carefully so. This work on silk of 1072 is thought to represent his mature, rather than late, style. Note the comical figures to the right and the humorous family to the left, which establish a human tone. Though a professional painter, Kuo became a great individualist model for the Yuan masters. He has created here a work whose effect is emphatically not singular but rather experiential.

By which I mean that the eye must move through the work in time, savoring its details, as the viewer almost loses his way. If Fan Kuan is massively objective, Kuo Hsi is diaphanously subjective. In this he has most in common with Southern Sung painters like Ma Yuan (active 1200), his son, Ma Lin, and Hsia Kuei, the former two part of a dynasty of academic painters. Kuo Hsi, however, is not an academic but instead one of the great originals in the history of Chinese painting. He and Fan Kuan seem to divide the world between themselves, until, that is we come upon a third hanging scroll, also immense in scale, also in Taipei’s National Palace Museum. I am speaking of the work on the far right above, Li T’ang’s Whispering Pines.

Li T’ang lived about 1056-1130 and so is much later than Fan Kuan or Kuo Hsi. Said to have been “persistently dependent upon” Fan, he is like him a “realist,” but one who moves in his work from the actualization of form to the actualization of spirit. For Li T’ang is Buddhist, and his treatment of nature has about it an attitude, as well as an allegorical program of purity, meditation, even Nirvana. In short, it portends another value system, another world. Instead of attending to my remarks, however, I encourage the reader to leave this paragraph behind, click to enlarge the image and spend some time exploring it alone, before returning.

Now we may approach the literati masters of the Yuan, Ming and Ch’ing. In the Yuan (or Mongol) Dynasty we will be taking up what are referred to as the Four Great Masters, Wu Chen, Ni Tsan, Huang Gung-wang and Wang Meng (I have placed the third of these out of chronological order, for reasons that I will explain when we come to him). In the Ming Dynasty, we will be looking at Shen Zhou, perhaps its greatest painter, and his greatest student, Wen Cheng-ming, plus Tung Ch’i-ch’ang, China’s most original painter and critic. In the Ch’ing Dynasty we will be looking at Wang Yuan-ch’i, one of four painters surnamed Wang.

In what follows I offer a three-part segment for each of eight painters: A. a brief biographical introduction, B. half a dozen examples of his work and C. very brief comments on each of them. C. will bring to bear upon these literati paintings observations of Kant’s regarding Space and Time; Actuality and Experience (Erfahrung); Cause and Effect; Motion in relation to Reality and the Self; the Empirically Real and the Transcendentally Ideal; Self-Positing and Self-Knowledge; “The Original Spontaneity of the Power of Representation”; the Imagination; and Knowledge, Understanding, Reason and Experience.

Wu Chen (1280-1354)

Originating in Chekiang Province, Wu Chen did not start to paint till the age of 37. His earliest extant work dates from a.ae. 48, which in part explains our sense of his maturity and mastery. “The master,” it is said, “lived hidden in the country. During his lifetime he enjoyed fishing, reciting, singing, writing and painting. When nearing death he built his own tomb — emulating those who in antiquity were intelligent about life and understood the decree of Heaven.” Wu, says a critic, “followed the Tung Yuan school but with less naturalism and more abstraction, focusing upon a dynamic balance of elements and personifying Nature in his work.”

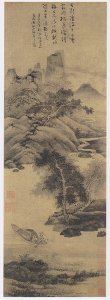

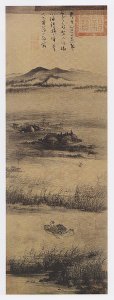

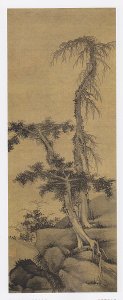

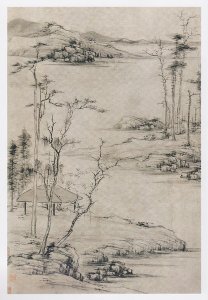

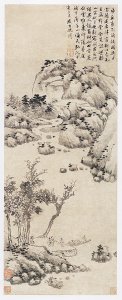

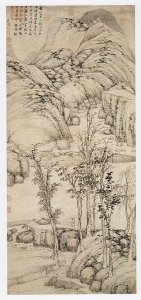

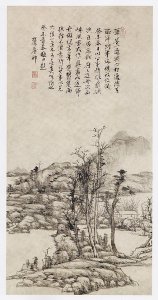

My favorite Chinese painter, Wu Chen is hard for me to talk about analytically. My selection omits two or three of his most famous landscapes (plus his calligraphy and bamboo painting). (1) shows man relaxed but at work and in motion, against a background of subtly graduated, metaphorical trees. In (2) he is dominated, like the lake, the near ground trees, and even the distant mountains, by an overwhelming cliff. (3) is in a different mood altogether, its ropy stone magically reminiscent of Huang Gung-wang. (4) is unexpected, its almost grotesque forms relieved only by a pathway leading (almost) out of them. (5) is contemplative, its near, middle and far ground make literal and explicit the Buddhist metaphor of this shore (Samsara), the farther shore (a Nirvana become Samsara), and a yet farther Nirvana. (6), with its Yin tree poised balletically against its Yang counterpart, plays off against Li Ch’eng’s paired trees.

Ni Tsan (1301-1374)

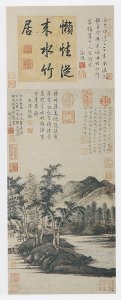

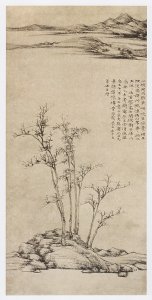

I have placed second this master of the frugal, remote, cool and thin. In time he came to be regarded as greater than Chao Meng-fu, whom he rivals in originality if not variety, Huang Gung-wang, who also preceded him in contemporary regard, and even Wu Chen (to my mind a greater painter). Born to a family of wealthy merchants in Kiangsu, surrounded by antiquities and books (he was a poet and collector as well as a renowned calligrapher), Ni Tsan suddenly distributed his possessions and departed for 20 years. His dated works (1339-1372) show little development but instead a relentlessly radical air of supreme refinement and purity.

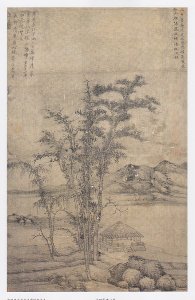

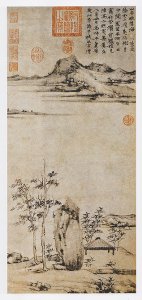

Kant says that transcendental judgment is achieved through a priori reason and a synthesis of imagination. Thus are Ni’s paintings a priori and synthetic. (1) I have looked at for 20 years without exhausting it. A pavilion too low to stand beneath intertwines two of its supporting posts with two improbably scraggly trees, next to which a third rises almost to touch a distant shore made of attenuated strokes. (2) contrasts this with a fecundity to be seen again in Tung Ch’i-chang’s imitation. More characteristic is the relentless repetition of (1)’s motifs in (3)-(6). In (5) the pavilion is credible but the trees are not. In (6) the trees are credible but the solitary stone outcrop and pavilion are not. (4) represents a further removal of the spirit, its expanse almost sandy rather than watery. It introduces a credible pavilion and four shores, which it fantastically connects (the 1st, 2nd and 3rd, the 2nd, 3rd and 4th ).

Huang Gung-wang (1269-1354)

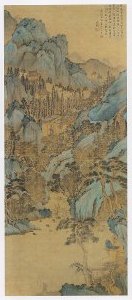

About the first Yuan master of mountainous landscape, more traditional than Wu or Ni, western and Chinese taste agree, the former finding in his facture a sensuous impressionism (Huang actually labored for years to achieve these effects), the latter finding something quintessentially Chinese. (He grows out of Tung Yuan and Chu Ran as transformed by Chao Meng-fu into a highly influential amalgam of virtuosity.) “A painting,” said Huang, is nothing but an idea, [and] what matters most when making [one] is the principle of rightness.” In this we have the same linkage between the philosophy of perception and ethics that we find in Kant’s Aesthetic Judgment.

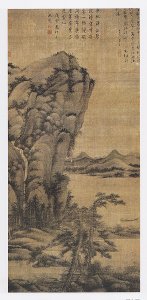

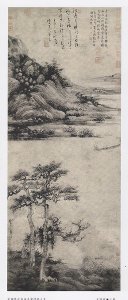

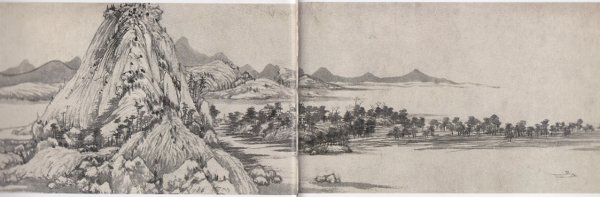

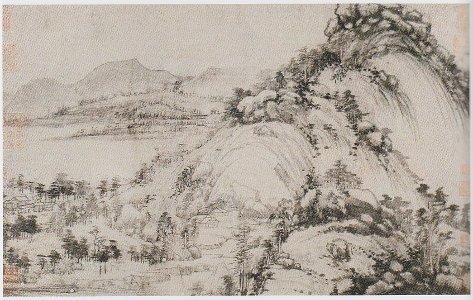

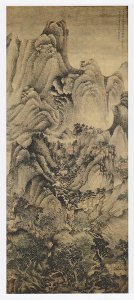

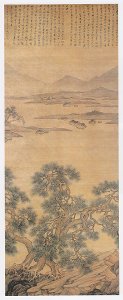

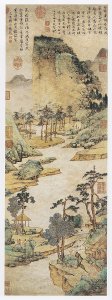

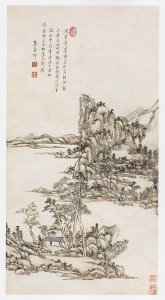

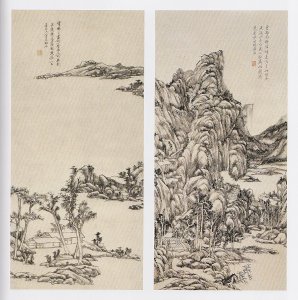

Though an impressive painter of hanging scrolls, Huang is known today principally as the creator of the Fu-Ch’un-Shan Chu Tu (literally, Living in Happiness Spring Mountains Painting), a long, evocative, experiential hand scroll, which exists in the original and in a copy, only parts of which, (1) and (2), can be reproduced here. In (2) we can study Huang's characteristic brushstrokes. I have placed two versions of a hanging scroll by Huang Gung-wang side by side, (3) and (4), smaller and larger. We notice in the smaller the mountain, in the larger the various pathways. Life is a process, a journey (we like to say), or, in modern terms, a movie. Huang Gung-wang prefigures cinematic technique by six centuries. Though the hanging scroll requires the eye’s movement, the hand scroll requires the hand’s motion, to unroll, and roll up, our experience.

Wang Meng (ca. 1308-1385)

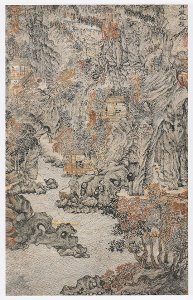

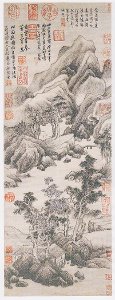

Distinctive from other Yuan painters (so much so that he was not recognized in his lifetime), Wang Meng was like the other literati in being a part of a close-knit, even in-grown, family of wealthy recluses who disdained public life. He was the grandson of Chao Meng-fu; the son of a collector for whom Wu Chen had painted an album; Chao Yung was his uncle. Wang’s work came to be highly regarded in the Ming (Tung Ch’i-ch’ang copied his paintings) and the Ch’ing (which paired him with Ni Tsan). From an overlay of fusty strokes he creates mountains that read as colossal organisms, “visible keys to invisible realities,” as a Yuan critic called them.

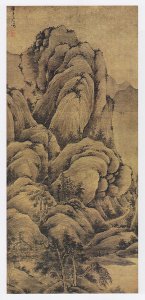

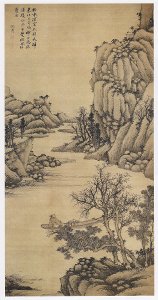

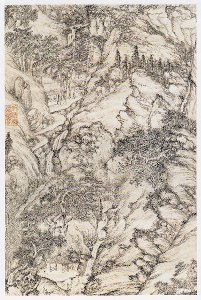

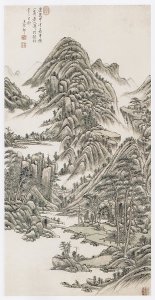

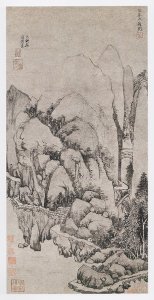

Wang’s work exemplifies Kantian “self-positing” and “self-knowledge.” (1)'s mountainous forms are like folds of flesh (or forms out of Ching Hao). (2) startles us with its concave-convex ambiguities. (3) creates the dorsal ridge of a Sphinx-like feline above an idyllic, companionable scene below the foothills, where one surrogate for the poet reclines on a dais, a poem in his hand, another fishes, yet another floats in a boat. In (4), (5) and (6) Wang’s innovations grow bolder yet. (4) runs the gamut from Heaven to Earth, from a monstrous face in the mountain to its echo in the hairdo of a gentle fisherman with his wife and servant. (5) compartmentalizes the world into never-before-seen, self-contained units, including a vaginal grotto on the right. (6) is the most ambitious treatment of Kant’s theme of Subject and Object, turning both world and self inside out, focusing on the latter below, on the former above.

Shen Chou (1427-1509)

The Ming was dominated by two schools, the Che (professionals) and the Wu (literati), the latter founded by Shen Chou, part of another tetrarchy, including his pupil, Wen Cheng-ming and two professional painters, T’ang Yin and Ch’iu Ying. Born wealthy, Shen was a Confucian scholar, a collector of late Yuan and early Ming paintings, which he and his colleagues used as models, along with works by Sung and Five Dynasty masters. His own painting is prefigured in feeling tone by Wang Fu, his poetry by Po Chu-i, Su Tung-p’o and Lu Yu. Departing from tradition, Shen Chou often painted actual places but rendered them poetically.

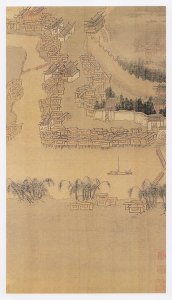

For Kant, Space and Time are the necessary conditions of “sensitive knowledge.” Shen’s oeuvre disguises its erudition in bodily form, painterly and attractive, as in (1), where the gentleman-scholar represents Good Humor. (2) renders a familiar landscape motif human with Shen Chou’s introduction of a sociable party, a guest bidding farewell to his hosts in view of an actual mountain. Thus Space and Time, for Shen as for Kant, are empirically real but transcendentally ideal. Shen also represents human relations, as had Li Ch’eng and Wu Chen, in terms of the entanglement of trees (3) or, of the unprecedented relationship of actual houses along the West River (5). Space and Time, for Kant, are the preconditions of Existence (not the other way round). They are also the preconditions of painting. A poetic boater gently floating in (4), and the scholar strolling in (6), construct nature, as in Kant, through their consciousness.

Wen Cheng-ming (1470-1559)

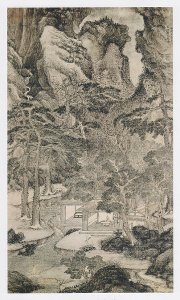

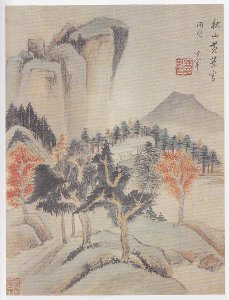

Though he deliberately diverged from Shen Chou, his master, Wen Cheng-ming had much in common with him. Wen too was a sociable Confucian. (His paintings frequently represent literati gatherings.) Like Shen he had many talents. (He designed with others one of China’s four greatest gardens; he was a great calligrapher.) Though he had in his youth repeatedly failed his exams, he eventually became a man of learning and exquisite sensibility, more like the Neo-Confucian Chu Hsi than Confucius. Wen Cheng-ming did not start painting till he reached 66. An admirer of Chao Meng-fu, early in life he had studied the Sung and pre-Sung masters.

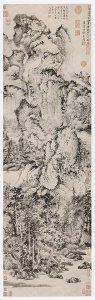

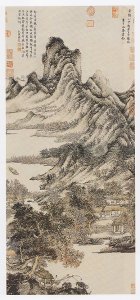

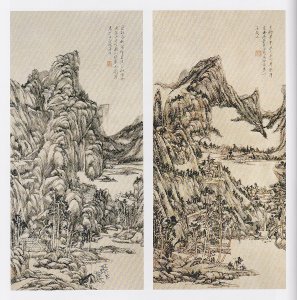

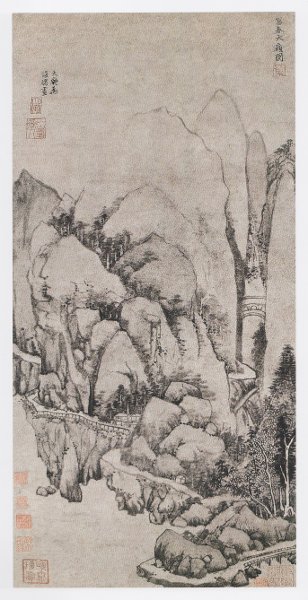

As for Kant his Categories are formative, so for the literati painter his Traditions. In (1) the painter reverts to the color scheme of the T’ang and elaborately varies the Yuan motif of multiple shores. With his outstretched hand a scholar on the left gestures backward in time. (2), titled Imitation of Wang Meng’s Landscapes, amalgamates many traditions, as had Wang Meng. In (3) a scholar returns from a writing expedition with his servant, who bears his calligraphic materials. In (4) Wen Cheng-ming disposes of his shores as a Five Dynasties or Yuan painter would have done, rendering them even more pointedly allegorical. (5) takes the menacing overhang from Wu Chen and exaggerates it to extreme, perhaps political, effect. (6) recombines T’ang color, Sung monumentality, late Yuan complexity and early Ming professionalism in a scene that focuses on two scholars caught on a bridge in a moment of leisurely conversation.

Tung Ch’i-ch’ang

Tung Ch’i-ch’ang, through an art historical energumen both critical and painterly, deliberately appropriates tradition and single-handedly transforms it as no other Chinese has ever done. Immensely learned and lettered, a compiler of history, Tung also became China’s most celebrated calligrapher, his models Mi Fei and Chao Meng-fu. As a painter, however, he breaks with his early models, Huang Gung-wang and Tung Yuan, to revitalize the whole tradition in work of breathtaking, sometimes disturbing, originality. Tung, who ran away from home at sixteen, produced an oeuvre with no pattern of development, one that is rarely in repose.

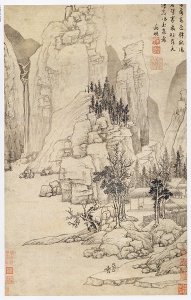

There are no human figures in Tung Ch’i-ch’ang’s work, no narratives. His subject was style itself. The alternation of traditional models and their transmogrification for Tung represent an assertion of individuality. Like Kant he pursues a progression that leaves only the Self, denying us the symphony of actuality. We begin in (1) with an already original style. In (2) the transformation of earlier motifs is bold and almost off-hand. In (3), titled Imitation of Chao Meng-fu’s Autumn River, Tung takes the transformative process a step further, producing a work that bears little if any resemblance to the work of Chao Meng-fu. (4) purports to be an Imitation of Classical Landscape but so violently transforms nature so as to render its geological dynamic instead. (5) carries Wang Meng’s ambiguities to an extreme in the guise of imitating Tung Yuan. In (6) we achieve a momentary, but still dynamic, quietude.

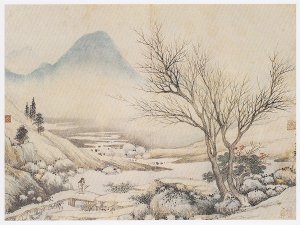

Wang Yuan-ch’i (1643-1715)

One of four Ch’ing Dynasty painters who summarize the tradition, all surnamed Wang (the others Wang Chien, Wang Hui and Wang Shi-min, his grandfather), Wang Yuan-ch’i, though related to them in their belatedness, is much more original. Unlike Shen Chou and Tung Ch’i-ch’ang, Wang Yuan-ch’i never copied a single work by an earlier master. Though he professed to be following the Yuan masters, his works often bear little resemblance to specific objects of emulation. Like Tung Ch’i-ch’ang he was engaged in a submerged struggle to overgo tradition. A Ph.D. at 28, he compiled a 100-volume work on painting and calligraphy.

Wang Yuan-ch’i adopted Huang Gung-wang’s ocher pigment and in (1) imitates his manner with a suavely organized composition. The literati are painters of Knowledge, Understanding, even Reason and hence are also painters of Experience (Erfahrung). In (2) Wang takes on Ni Tsan but lowers his vantage point so as to view Ni’s scraggly trees against a this-worldly rather than other-worldly background. Kantian Experience is conceptual, as is (3)’s orderly disposition of the myriad and various natural elements. It transforms antecedent Nature by an act of Human Will, as in (4). It is consistent with Science, is itself an “earth science,” as in (5) and, Kant says, is necessary to the whole enterprise of Science. Finally, Experience imitates earlier Experience (painting), as in Wang’s late imitations (6)-(9) of Huang Gung-wang, Wang Meng, Ni Tsan and Wu Chen, the first and last paintings here virtually identical.