Pattern as Cosmology in Geometric Islamic Art: 2

Introduction

George Michell and Amit Pasricha’s Mughal Architecture & Gardens (Woodbridge: Antique Collector’s Club, 2011) is said to be the first comprehensive monograph on the subject in 20 years. It is a magnificent book, one which incidentally places the Taj Mahal in its political, historical and architectural contexts. The authors take up this familiar monument first in a paragraph, then in a disquisition accompanied by glorious photographs. Since I have never, in six trips to India, visited the Taj, I especially appreciated the interior views.

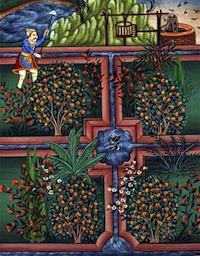

Instead of dully recapitulating the by now rather well-known history of Babur, Humayun, Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan, or by rehearsing the famous myth of the Taj Mahal’s romantic origins and execution (in honor of Mumtaz Mahal, the emperor’s love), I will quote a few sentences of observations (rewritten as always for our purposes) not about the Taj but about more general matters. The so-called “char-bagh” is the garden layout divided into four geometric units, as in the forecourt to the Taj, sometimes subdivided for tombs into sixteen.

On the char-bagh

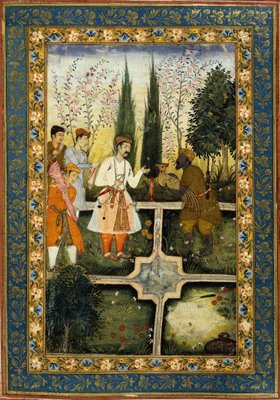

The Mughals were always haunted by the memory of their Central Asian origins, though they settled permanently in India after Humayun’s triumphal return in 1555, never to see their mother country again, they continued to nourish the image of an arid, rugged landscape with mountain springs and streams that could be harnessed to cultivate diverse fruit bearing trees and flowering plants in high-walled compounds.

The legacy of Babur

Babur’s love of flowers, fruits and trees was continued under his successors for whom the building of gardens developed into a major enterprise, employed for tented military encampments and pleasure resorts outside the major cities, as well as for private gardens within vast palace complexes, and for the great dynastic tombs that so often represent the architectural pinnacles of accomplishment in the Mughal age.

The first great char-bagh

Humayun’s tomb had the first. Covering an area of more than 360 meters on each side, the garden is divided into 6 by 6 equal square plots, a design never to be encountered again in the entire history of Mughal gardens. This unique layout may be interpreted as reflecting the effort made by Akbar and his Persian master architect to synthesize Central Asian and Indian traditions, thereby serving as setting for a major monument.

The next project

The next great funerary project of Mughal architecture is the mausoleum erected by Jahangir for his father Akbar at Sikandra, which reprised a more conventional char-bagh for its garden setting. Even more extensive than the garden of Humayun’s tomb is that in which Akbar’s tomb stands; this measures no less than 700 meters on each side, making it by far the largest in the history of Mughal garden design.

Ornamentation of the tombs

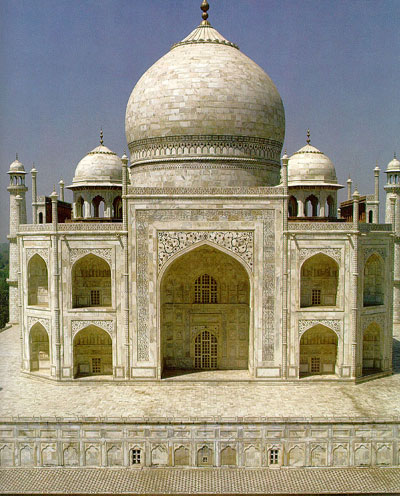

A love of geometry infuses all aspects of Mughal architecture and its ornamentation. Stones of different colors laid in infinitely expanding patterns created from interlocking hexagons, contained in arched frames, geometric patterns that are developed into designs based on triangles, six-pointed stars and pentagons and into ten-sided stars. Mathematically determined, elegantly interwoven lattices are another instance of geometric design.

Since we are blessed with such an authoritative text, I will continue by quoting from the pages about the Taj Mahal in Michell and Pasricha:

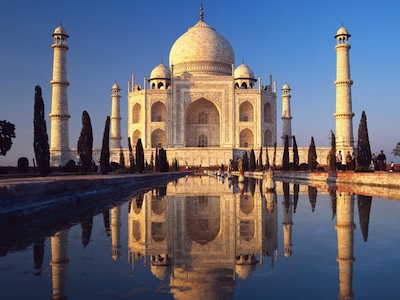

The mausoleum of Mumtaz Mahal and Shah Jahan, known throughout the world as the Taj Mahal, is referred to in contemporary Mughal texts as Rauza-I Munavvara, or Luminous Tomb.

The huge scale of the Taj Mahal testifies to the sustained building work that Shah Jahan was able to finance over a period of almost 12 years. And it was here that he himself was buried 23 years afterward.

While the visual climax of the complex is the white marble mausoleum rising upon a terrace at the northern end of the garden, it is the great char-bagh that forms the spatial centerpiece.

Walkways subdivide the char-bagh’s quadrants into four, thereby creating sixteen plots in all. The east and west perimeter garden walls have corner towers with octagonal chhatris (open domical pavilions).

The four corners of the podium are punctuated by cylindrical minarets crowned by chhatris. More than 43 meters high, the minarets are built to tilt slightly inward so as to appear truly vertical.

We will return to the Taj Mahal in section 2B. of this presentation, but lest we lose sight of our principal topic, we now turn to the uses of numerology in Islamic architecture.

Pattern as Cosmology in Geometric Islamic Art: 2A

Numerological design in traditional Islamic architecture

In his Islamic Geometric Patterns (London: Thames & Hudson, 2008, reprinted 2011) Eric Broug takes the dominant abstract decorative designs in nineteen of the most famous Islamic monuments/texts, orders them according to degree of difficulty, shows how they were constructed and presents them in his book, then excerpts eight of them for the CD. This morning Hassan, my Pakistani tutor, and I chose four of these for detailed study, to wit:

(1) The Great Mosque of Cordoba (Cordoba, Spain, AD 784)

(2) Musansiriya Madrasa (Baghdad, Iraq, AD 1227)

(3) The Cappella Palatina (Palermo, Sicily, Italy, AD 1132)

(4) The ’Abd al-Samad Complex (Natanz, Iran, AD 1304)

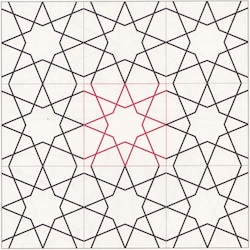

(1) The figure for The Great Mosque of Cordoba (“La Mezquita” in Spanish), which I have visited, “underwent many changes between AD 784 and AD 987.” According to Broug “it emulates the architectural styles of the Umayyads of Syria (AD 661-750) and the early Abbasids of Iraq (AD 750-1258).” According to Hassan it uses what he calls the “infinity design,” whereby the repeated pattern continues beyond the frame that generates it and so indicates the infinite cosmos. “None of the lines in this design,” he observed, “are broken. The design is conceived as a circle (the cosmos) within a square (a more basic mold).”

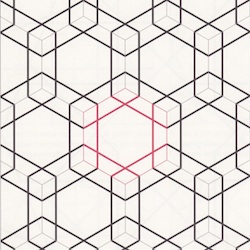

(2) The Mustansiriya Madrasa (which means “place of study”) was built by the Abbasid caliph al-Mustansir; it “was the first college to be dedicated to all four Sunni schools of law.” A building of two stories built of rectangular brick, according to Eric Broug, “it consists of eight groups of cells symmetrically arranged over two floors around a central, elongated courtyard and is exquisitely decorated in places.” Hassan again noted the “infinity design,” and its “hexagonal theme,” which is cubic (i.e., it imitates the six faces of that figure). The result is a hexagon that embodies a cube, whose thick walls it represents in perspective.

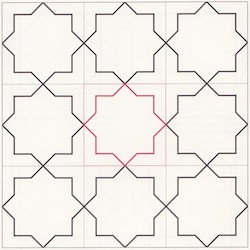

(3) The design of the Cappella Palatina is quite striking, as befits the patron of this royal chapel of the Norman kings of Sicily in Palermo’s Palazzo Reale. “Commissioned by Roger II of Sicily in AD 1132, it took eight years to build and many more to complete the elaborate decor,” says Broug. “The chapel blends a variety of different styles, from Norman architecture and adornment to Arabic arches to Byzantine domes and mosaics.” Its wooden ceiling has clusters of eight-pointed stars arranged in the form of a Christian cross.” Hassan’s comment: “The people who designed this were very concerned with the cosmological theme.”

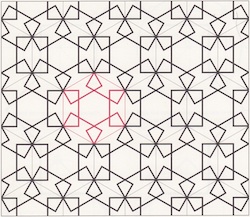

(4) The last example that Hassan and I examined is the design that decorated the ’abd al-Samad complex in the ancient town of Natanz, which has “the oldest dome in central Iran.” ’Abd al-Samad “was a mystic of the Suhrawardi order and lived near the mosque” (Broug). “After his death the building was enlarged with a wonderful shrine complex comprising ’Abd al-Samad’s tomb, a muqarnas vault and a khanaqah,” i.e., a monastery. The theme of the design is a combination of rectangles and hexagons. Hassan described its feeling as “a description of things in nature or our natures that are seemingly disordered but have order.”

*

Despite the Pythagorean meanings ascribed to the numbers, a design based on one such primary number is not “explained” by the Pythagorean gloss, though some of the Pythagorean meaning is relevant. The patterns, that is, are not symbolic, much less complexly allegorical. In his Sufism, Carl W. Ernst says of the revelation of Muhammad that it “is self-authenticating.” Likewise, we might say that geometric Islamic patterns are self-authenticating. There is a relationship between the abstract patterns of Islamic geometrical art and calligraphy.

The Qur’an itself frequently alludes to the pen and to writing, generally in contexts that emphasize writing as a medium for conveying the divine message to humanity. The earliest Qur’ans exhibit large letters on parchment in the austere yet graceful Kufic style; the relatively small number of words on the page appear more like a visual icon than an ordinary book.

Welch: “The written form of the Qur’an is the visual equivalent of the eternal Qur’an and is humanity’s glimpse of the divine.” Sufism and geometric art share something else: a universality. On Sufism’s universality, Ernst offers an historical anecdote:

Some have defined Sufism as the universal aspect of all religions. A striking example of this universalist tendency is the life and legacy of Hazrat Inayat Khan, who came to the West in the early years of the 20th century. Trained both as a musician and as a Sufi in the Chisti order, he traveled in Europe and America giving performances of classical Indian music. Faced with the need to articulate a religious position, he presented Sufism as a universal religion, detached from Islamic ritual and legal practice.

Perhaps the Taj Mahal transcends in its universal appeal its Pythagorean numerology and, like Sufi doctrine and Arabic calligraphy, appeals to a mystic sense of perfection. There follows another discussion relevant to its widespread popularity:

Pattern as Cosmology in Geometric Islamic Art: 2B

The arrival of the Mughals and architectural characteristics of their tombs

(Information and modified quotations from an article available on the Internet, titled “History, Morphology and Perfect Portions,” drawn to my attention by my tutor)

The Mughals invaded India in 1400; the period of investigation in the article is 1480-1858. The new style of architecture blends Islamic, Roman and Hindu styles. These tombs were influenced by Martyria, churches dedicated to saints’ relics; by Greek and by Roman mausolea. Several great tombs precede Taj Mahal, the two most important: Nasiruddin Humayun’s and Akbar’s.

Humayun’s, the first stone tomb, was completed in 1571. It was built by his son to establish visually the presence of the Mughals in a foreign place (New Delhi). The authors emphasize the importance of the garden as evidence of the Mughals’ ability to tame the Indian landscape with lush vegetation and maintain it. The second tomb is at Sikandra, outside Akbar’s capital of Agra.

It displays the ability of his empire to absorb multicultural influences while remaining true to his roots. It was followed by the Taj Mahal, completed in 1632, a monument built by Shah Jahan for his wife. It is the only such mausoleum that was built by a ruler during his lifetime. The plan is more complex than any of its predecessors. It is known for four features.

(1) The use of the char-bagh (a paradisal garden), which in Urdu means “four gardens,” the four quarters into which the square that stands before the tomb is subdivided. The char-bagh is said to be heavily influenced by the Persian style. In the Hindu interpretation of Mount Meru, rivers flow in all four cardinal directions from a “cosmic cross.” Similar is the Mughal view of the matter:

The char-bagh is seen as a manifestation of the four rivers that flow through Paradise. The most original feature of the Taj in terms of its planning was to move the mausoleum back from the center of the char-bagh to the edge furthest from the river, next to which it was situated (to benefit from the cooling effect of the waters and to create a benevolent effect upon the char-bagh itself).

(2) The second feature is the complex use of the nine-fold hasht-bihist’s plan. “Hasht-bihist” means literally “eight paradises” (in Urdu). The overall plan of the Taj is a square with four chamfered corners, which create the eight sides of an irregular octagon. These chambers are ranged about a central ninth room. At this point we might consider the ground plans for three other major tombs.

Humayun’s Tomb has four chamfered octagons in the corners of a cross at whose center a diamond, within which a square divided by two diagonals. Akbar’s Tomb is much simpler in plan: It consists of a square with surrounding walls, at the center a much smaller square and a passage to and through it. Imad’s Tomb, a square divided into nine parts, has tiny octagons outside its corners.

(3) The tombs reflect a hierarchy of building materials, in the case of the Taj Mahal: white marble, red sandstone, black onyx and marble (Jali) screens. On these were applied semi-precious stones.

(4) The authors of “History, Morphology and Perfect Proportions” summarize the careful planning of the entrance to the Taj Mahal thus: “Approach through the courtyard and garden is carefully orchestrated with more subtlety than at any other of the monuments. The location of the structure at the end of the garden means that it occupies the highly visible spot on the river which dominates the skyline . . . ”

(5) Of interest to the numerologist, especially to one studying the numerology of Islamic geometric art, is the following discourse on the significance of the five parts of the Taj Mahal's facade:

Five is a sign of harmony and balance. It is also the symbol of the human being, which with arms outstretched in the shape of a cross appears to comprise five parts. It is also a symbol of the universe, its two axes passing through the same center. Moreover, it stands for the phenomenal world in its entirety, for the five senses and for the forms of matter amenable to sense perception. Five is a lucky number, the number of the hours of prayer, and the types of goods upon which tithes are payable; there are five elements in the hajj (pilgrimage), five types of fasting, five motions for ablution, five dispensations for Friday . . . There were five witnesses to the Mubahala (treaty) and five keys to the Koranic mystery.

In the Conclusion the authors write: “Taj for the first time uses the perfect 1:1 ratio in both plan and elevation to create a perfect cube, which sits among the minarets in a 1:2 ratio to create a balanced, harmonious composition surrounding the central dome. Triangulation is present in all four mausolea as a tool that takes the focus from earth to heaven.”

About the Taj Mahal’s number symbolism, Hassan said: “The most important numbers of religious significance are 4, 8 and 9. Shah Jahan’s, like Humayun’s, Akbar’s and Imad’s tombs before it, are all designed fundamentally as squares. Their four sides, in the thinking of Islam, correspond to the Four Holy Books and the Four Messengers. The Taj has a floor plan consisting of eight rooms about a central room, number 9. The 8 represents the Eight Heavens of Islamic cosmology, whereas the 9 represents God. Imad’s Tomb is organized as a square with nine divisions. Shah Jahan’s interior is octagonal; that of Humayun’s includes four octagons; Imad’s Tomb has four tiny octagons placed just outside each of its four corners.”

Pattern as Cosmology in Geometric Islamic Art: 2C

How to interpret a work of Islamic architecture?

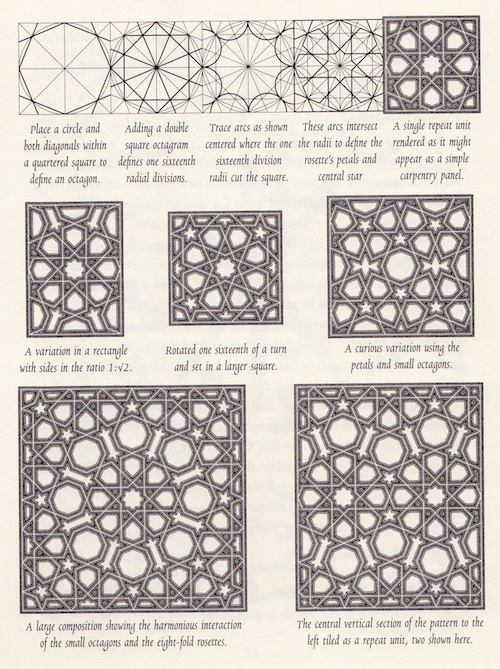

This discussion follows upon one in which I raised the question of how to interpret abstract works of Islamic geometrical art, about which most earlier commentaries seem to have been lost. Accordingly today I raised the question with Hassan, in relation to the interpretation of a single figure in David Sutton’s Islamic Design, one that occurs in “Eight-Fold Rosettes and some construction principles” (p. 11). This figure is accompanied by four variants, so I thought that it might be possible to compare Hassan’s interpretation of related figures too.

“The Qur’an,” he said, “permits freedom. People have freedom in their lives,” he continued. “One should show people the wishes of God but not criticize the people.” “Each person has his own view and his own freedom to exercise it.” When I inquired about the arts, he said, “Likewise, the creator of patterns too has a freedom. Every artist may create his own designs within the terms of tradition.” As for the Islamic viewer of Islamic art, “He has freedom of interpretation. Of course,” Hassan added, “he may be wrong, but this is a different matter.”

The problem arises in the actual interpretation of specific works. For weeks I have tried to pin my tutor down on what a given work “means,” i.e., how to interpret it. He will say, “This work is beautiful”; of another work, “It expresses the infinite.” I am reminded of a story about an oral Ph.D. exam at Harvard. The Japanese candidate was asked by the chairman to comment on Keats. Pausing interminably, he drew a deep breath and said, “Keats . . . beautiful!” The examiners nodded in dismay. Asked next about Shelley, he said: “Shelley . . . marvelous!”

After a few more minutes of this, the chair asked Mr. Yamamoto to step out into the hall. “Mr. Yamamoto,” he said, “after you receive the Ph.D., do you plan to remain in the USA or return to Japan?” “Go back Japan,” said Mr. Yamamoto. Extending his hand, the chair said to the candidate, “Congratulations, Mr. Yamomoto, you have passed.” The problem, as James Cahill notes with Chinese landscape painting (and we with the Japanese student’s brilliant answers), is that there is no native criticism of Chinese painting, or of Islamic geometric art.

Returning to the example at Sutton,11, I asked of Hassan: “What are the characteristics of a work of Islamic art that make us feel that it expresses freedom? He re-enunciated points that he had already made: “The work has a closed border; it is not a work of infinity”; “the variety of figures expresses freedom”; “the work shows imaginative variations of the octagon”; “so, many religious beings in the world, so, many cultures.” “It can serve as the expression of Islamic theology,” he added, “but it can also serve as an expression of the world’s variety.”

Hassan clearly did not grasp the meaning of my request that he criticize Islamic art. When asked the significance of a work based upon a seven-sided figure, he said, “Seven is a great religious truth; it is also a secular universal”; “just as there are, in the Muslim way of thinking, seven layers of heaven (not visible) through which one must pass to attain God, so there are seven actual layers of earth.” I asked Hassan to explain to me the difference in feeling of a seven- as opposed to a six- or an eight-sided figure, but he could not understand my question.