Pattern as Cosmology in Geometric Islamic Art: 4

Introduction

Although I have carefully gone through three of the leading texts on Islamic geometric patterns and their construction, by Critchlow, Broug and Sutton, I am also heavily indebted to my Pakistani tutor, Hassan, in subsequent efforts to understand Islam, its religious doctrines and philosophical traditions and their relationship to its unusual, exhilarating geometric art. I will confess that I have devoted too little study to the Qur’an, though I have read books about it, about the historical development of Muslim theology, as well as about Islam more generally.

The day that I met him at his restaurant, Hassan began by talking about the Qur’an. After our conversation I returned home and recorded from memory several points of his:

- “The Qur’an is universal”

- “Its language has remained unchanged”

- “Therefore it is geographically and historically true”

- “When translated, its text still remains unchanged”

- “It is true of the individual and of the cosmos”

- “It is both historical and trans-historical”

On my second trip to Omar Khayyam Restaurant in Pattaya, where Hassan was serving as manager, I raised with him the narrower subject of my new “Special Topics” presentation, “Pattern as Cosmology in Geometric Islamic Art.” Hassan began with a commonplace: “Mathematics allows for precision: in the realms of time, matter and natural law.”

- We may discover Islam through mathematical induction

- We may approach the mind of God through its perfection

- Man himself, by using metrics, can approach perfection

- The science of numerology bears upon the Conduct of Life

- The archetypes, as Critchlow says, control our biorhythms

- The archetypes also control the architecture of the Cosmos

- Though the exteriors of mosques differ, their interiors are similar

- Each, through the Qibla, indicates an orientation toward Mecca

- In Mecca the cubic form of the K’aba stands at the world’s center

- Within its square is inscribed a circle, within the cube, a sphere

- The radii of the circle and the square indicate two-way directions

- They lead from the world to the center, therefrom, to the periphery

- This view of the K’aba begins with Abraham and his son, Ismail

- It was they who imaged the emanation of Islam into the world

- For the world of Islam the K’aba is thus a geometric universal

Pattern as Cosmology in Geometric Islamic Art: 4A

The Geometrical Forms, in consecutive sessions with Hassan

(for the triangle, see the final page of the general Introduction)

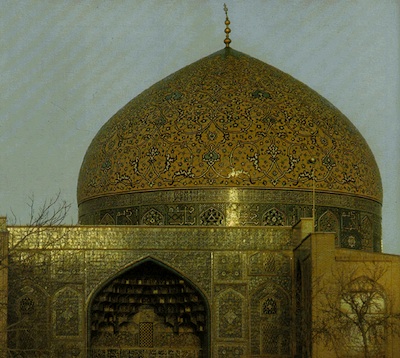

Busy with other matters this morning, Hassan had only 45 minutes but will see me again tomorrow. He began today's session where the last left off: with the triangle. A friend had told him that the pyramid, the simplest of the polyhedra, has been historically prized, but in the Islamic World it has has been regarded as attracting ill fortune, in contrast to the hemisphere, which forms the dome of mosques, and the semicircle, a common form of their arches and decoration.

The pyramid, or tetrahedron, was also, he said, regarded as inauspicious. One wonders if this way of thinking has to do with ancient Egypt. Hassan remarked that the hemisphere and semicircle were common to Hindu, Buddhist and Christian as well as Islamic tradition. From the triangle we moved on to the square and the pentagon. I sought Hassan's views of both. “The square,” he began, “belongs to the construction of buildings and to the subdivision of the land for agricultural purposes.”

“It is superior,” he said, “to the rectangle, a fortiori, to the circle, in the construction of buildings, as the strongest design principle.” Turning to the pentagon, he interpreted its five corners, reading them clockwise, as corresponding to the five public prayers of the Islamic world: (1) at dawn (fajar), (2) at mid-day (zohar), (3) at the start of the sun’s descent (asur), (4) at sunset (maghrib), and (5) before one goes to sleep (isha). Thus it symbolizes the whole day, which one should spend according to God’s wishes.

Pattern as Cosmology in Geometric Islamic Art: 4B

Quotations from Keith Critchlow, Islamic Patterns: An Analytical and Cosmological Approach

(1) The overriding principle for Islam is the unity of existence and therefore of the universe. This unity has always an inner and an outer aspect ― a hidden as well as a manifest aspect. From this it follows that there is an inner as well as an outer way of studying cosmology. The outer embraces sensible observation, the inner is appreciating the expression of cosmological laws within one’s own structure. The goal of spiritual disciplines is to unite the inner and the outer, the greater and smaller, into an inseparable integrity.

The language of the archetypal laws which unite the inner and the outer cosmos is that of pattern and in particular number pattern.

(2) The philosophical perspective of Islam takes the patterns and periodicities of the heavenly revolution to be “moved” by the same archetypes as the mind of man which appreciates them. It therefore follows that as the Sun and Moon control the biorhythms of our bodies and influence our animistic psychology, so the archetypes control the rhythms of the heavens. By being in harmony with these rhythms, that is, by placing oneself at the center of them ― much as the nucleus controls a cell, or the center of balance maintains poise ― one can master them by being at one with them.

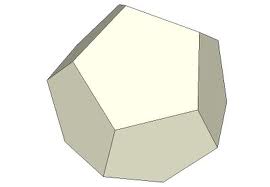

(3) The indication of periods of time and directions in space occurs in pattern form as intervals around the perimeter of this primal circle. For instance, the face of a clock with its twelve hourly divisions exemplifies the measuring of the passage of time with precision, whereas if one should join these same intervals on the clock-face with straight lines one would describe a twelve-sided shape ― a dodecagon. Both can be taken as expressions of the archetype twelve, and in cosmology they are united temporally and spatially in one complete annual cycle of our planet: the twelve zodiacal constellations give us both a directional guide and specific periods of time by which to measure the whole year.

(4) The next most important factor is the triangular relationship between Sun, Earth and Moon. The primal three as archetype represent the minimal conditions for existence, one, the other and the conjunction, or, put another way, the viewer, viewing, and the viewed, or object, subject and relationship. It has been suggested that the essential spiritual triangle in Islam is Allah, Rahman and Rahim, as they occur at the beginning of each sura of the Qur’an.

Three gives rise to six, and six has a vital role in Islamic cosmology as it does in the other two Abrahamic religions, Judaism and Christianity; and this role relates to the number of days in which God created the world. The Abrahamic wisdom insists that we regard the inner and outer meaning of the cosmogony, its symbolic and literal dimensions. The six-pointed star is a symbol of perfection in all three religions.

(5) Starting from the centers or point distribution, which are the notes of the Platonic figure known as the icosihedron, if we imagine these expanding to take possession of equal surface area in the domain of the sphere, they expand until they meet each other at five equally distributed points; if these points were joined, the lines would describe a spherical icosidodecahedron. If these domains or areas kept spreading without infringing the domain of the five neighboring domains, they would each eventually become pentagonal. This is the pentagonal dodecahedron, traditionally related to the universe by Plato in his cosmological treatise, the Timaeus, and embraced into the Islamic philosophical perspective by al-Kindi.

(6) Nasr develops this fundamental relationship between the Zodiac and the two archetypal numbers, 3 and 4. Possessing this basic relation with the four fundamental cosmic qualities, the signs are naturally related to all cosmic manifestations, which are themselves due to the various combinations of their qualities. Inasmuch as these combinations are limitless, the analogies to be drawn between them and the signs are also without end. However, he says, there is a hierarchy of values to this indefinity of combinations, and in relation to terrestrial existence the relation of the signs to the cardinal points of the compass are of considerable significance due to the role of “sacred geography” and orientation in sacred rites and the architecture of temples and other structures that are based on the knowledge of the “anatomy of the cosmos.”

In brief, the “heaven of the archetypes” stands outside the space of the manifest cosmos. Pure Being, which is meta-cosmic, is hidden by the signs, while at the same time its polarization is manifested by them. They contain the four qualities of Universal Nature and the three fundamental tendencies of the Spirit and therefore the archetypes, or “ideas,” of all the manifestations of Nature which we witness in the world.

(7) As the macrocosmic manifestation of the intellect, the planets must of necessity have a bearing upon all terrestrial beings which, like everything else in the cosmos, owe their existence to the Universal Intellect which in Islam is identified with the “light or reality of Muhammad.”

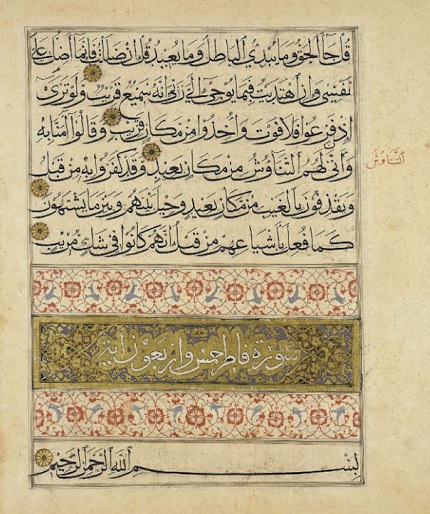

(8) Equally importantly, the lunar mansions are the macrocosmic counterpart of the twenty-eight letters of the Arabic alphabet from which the language of the Divine Word can be articulated as an expression of the Divine Breath itself. It is in this way that all events are written in the Book, the cosmos being the macrocosmic writing of the Sacred Book as the Qur’an manifests this Divine Revelation to the human world.

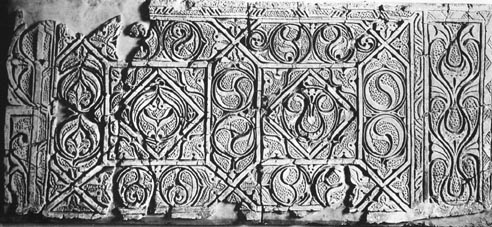

(9) It is here also that we can appreciate the profoundly esoteric way in which apparently “decorative” adornment of buildings in the form of geometric patterns reveals in the guise of symmetry the very laws of possibility in the manifest realm.

Thus Islamic pattern, unique as an art form, is also unitary in its aim and function.

(10) We now redraw the basic propositions within a qualitative and cosmological perspective. Each shape is representative of, and in its own realm embodies, the same archetypal principles as the cosmos and our consciousness that reads them both.

Thus the unfolding of the geometric laws in the realm of mathematics has a quality corresponding to the unfolding of both consciousness and creation itself.

Pattern as Cosmology in Geometric Islamic Art: 4C

Today Hassan and I spent some time on (5) and (6) of my summary of Critchlow’s observations. We also glanced briefly at (7)-(10), so that Hassan might have a chance to raise any objections. Critchlow he finds fundamentally correct. I have also been leaving with Hassan all the major treatments of my topic, not only by Critchlow but also by Eric Bourg and now by David Sutton, to let Hassan see if he has any reservations about this arcane material. I have asked that he respond, for my benefit, emotionally to the various severe patterns.

As for (5) and (6) in my summary of Keith Critchlow’s points, Hassan listed “the four major aspects of life,” Critchlow’s “four qualities of universal nature” (recall Critchlow’s thesis, agreeable to Hassan, that the inner life and the cosmos form a unity):

Water, Air, Food, Light

This he followed with a list of the three “ideas,” adding that the four elements are determined by the following three figures:

God, Mohammad, Human Beings

Hassan emphasized that the rules of behavior govern not only Muslims but “all human beings” (though on further inquiry it was clear that he hoped that all human beings would convert).

The four aspects and three ideas constitute “The Seven Aspects of Existence and its Spiritual Meaning.” Only Muhammad, said Hassan, was capable of fulfilling them 100 per cent.

“When we read his life, we see that he is following God’s will 100 per cent. To do God’s wishes, one must adopt Muhammad as one’s model. The goal is to meet God in Heaven.”

Whereupon Hassan turned to rules for the practical conduct of life

- Do not drink water when you are standing up. Sit down.

- Drink the water gradually, sip by sip, to quench your thirst.

Islamic prayer, he noted, likewise represents a physical process:

- First sit down, then touch one’s head to the ground.

- Then return to a sitting posture. It is a kind of exercise.

These practices, along with cleansing the face, the eyes and the back of one’s neck (and one’s forearms too) five times a day before prayer, were guaranteed to give good physical results.

Pattern as Cosmology in Geometric Islamic Art: 4D

Hassan made three generalizations about Islamic abstract art: (1) It is very traditional, (2) Its themes cannot be changed, and (3) Nonetheless, its technique is advanced.

In enunciating his third point he meant to say that the artist working in this tradition is always striving to do something new and original.

I asked him how he felt about these works and whether, when he viewed them, the underlying mathematics was visible. He said, by way of response, that abstract Islamic art, in its relation to Pythagorean mathematics, is like the working of a computer in relation to its binary program. Both function as substrata in the operation of art and machine.

Hassan mentioned the number 786, which, when placed at the start of a letter, is “very positive.” If it is followed by “bismallah,” it means that “we are beginning this work with the blessing of God.” “7 + 8 + 6 = 21, a ‘useful’ number,” he said, one that expresses “sympathy.” “When one gives gifts,” he said, “one gives 21 rupees or 21 more expensive gifts.”

The number 1 signifies God. As in other cultures, however, 13 is inauspicious.. As we began to look at patterns in David Sutton’s Islamic Design: A Genius for Geometry, at an example of foliate elements, Hassan said, “Plants in Islamic design signify the infinity of God.” When I responded, “Plants continue to grow,” he nodded in agreement.

Hassan emphasized that the strictly geometric patterns, which we next took up on pp. 3, 5 and 7, were symmetrical. We looked at designs based upon the hexagon. “1 + 2 + 3 = 6,” said Hassan, meaning that 6 embraces the first three numbers. In response to the development of the six-fold patterns, in stars and hexagons, Hassan said, “Beautiful!”

He responded in a similar way to the illustration of six different designs in the next chapter (titled “Sixes Extrapolated”), remarking that the theme remains the same but that each example expresses a novel solution, “as in nature,” by which he drew attention to the analogy between the variety of examples and the fecundity of natural processes.

I asked him to gloss two terms in Sutton’s text, “infinity” and “Divine Unity.” Two designs on Page 7 exceed their frame and so express “infinity,” he said. The fact that all were six-sided expressed their “divinity” or “divine unity.” He kept remarking upon how the designs were all different from one another. “The middle two are ‘very common.’”

Pattern as Cosmology in Geometric Islamic Art: 4E

Not all Islamic art is abstract (nor is all abstraction therein cosmological), but the general tendency from the earliest period is toward abstraction. Here through modified quotations from Robert Hillenbrand’s compact but magisterial survey, Islamic Art and Architecture (London: Thames & Hudson, 1999, rpt. 2010), I trace chronologically important steps toward abstraction both in the individual artistic traditions as well as in Islamic art more generally. His observations have been keyed by page number, so that those interested may read more:

24 In a far-reaching currency reform which extended to most of the Islamic world, carried out between 695 and 697, all figural images were expunged, to be replaced by the quintessential Islamic icon: Qur’anic epigraphy.

28 The Prophet’s house in Medina (“the primordial mosque of Islam”) recast standard components of a typical Christian basilica . . . and included, inter alia, carved marble window grilles with elaborate geometrical patterns.

38 The new Abbasid dynasty claimed to usher in the true Islam based on universal brotherhood irrespective of race. Such a doctrine, if it in fact preceded the art that embodied it, militated against representing specific races.

43 Art at Samara rejected classical naturalism. In a first new style, surface is divided into polygonal compartments with pearl borders; in a second, this tendency results in an art in which recognizably natural forms disappear.

60 Internationalization under the Abassids led to abstraction, which in turn led to the development of the arabesque. Within the empire there were no frontiers, which can be explained by a unity of faith and political institutions.

77 Under the Fatimids it was a tenet of Isma’ili belief that the Holy Family existed in the form of light even before the world was created. The Qur’anic inscriptions refer to the sun, the moon and the stars as the Sh’ite Holy Family.

95 Under the Seljuks sculpture took a turn toward abstraction, the body of the figures represented dematerialized and reduced to an inscribed, decorated surface. Thus the artist avoided usurping God’s prerogative of creating life.

139 The Mamluks established through politics and military conquest (preventing a Mongol takeover of the Near East) a claim to be the defenders of a single orthodoxy, thus inhibiting the development of alternative artistic styles.

140 Meanwhile, the primacy of Mamluk Egypt, opening onto the Christian Mediterranean cultures but also those of the Red Sea and India, enabled it to adjudicate the claims of rival civilizations and their forms of artistic expression.

148 The muqarnas ceiling, instead of a merely decorative surface, evolved into an artistic expression of major visual importance in Mamluk buildings and became a standard abstract architectural element throughout the Empire.

150 Under the Mamluks calligraphy became an increasingly formal means to express hierarchy and status; calligraphers found an ideal objective correlative to the court in this mannered script for official descriptions.

151 For similar reasons the blazon developed into an abstract form to express the various distinctions that all reveal a society obsessively concerned with rank and status as defined artistically in its emblems and identification tags.

224 Painters under the Timurids, like their predecessors, customarily favored the general at the expense of the particular, and their paintings, not realistic, testify as much to intellectual abstraction as to any patient observation.

264 Under the Ottomans, who assimilated Roman and Christian styles to Islam, though Haghia Sophia exploited a mystery and ambiguity, architecture generally took the form of display, emphasizing clarity and logic.

271 Late in the development of classic Islamic art, the image of Muhammad became abstract; images of Islam’s founder adopted a white veil and a gigantic flame halo, as though to attain a visionary intensity of an abstract nature.

Pattern as Cosmology in Geometric Islamic Art: 4F

Edited from Abdullah Saeed, Islamic Thought: An Introduction (London: Routledge, 2006)

The art of Islam is essentially a contemplative one, which expresses the divine presence. It is abstract and decorative and portrays geometric, floral, arabesque and calligraphic designs. The general lack of portraiture is due to the fact that the authorities of early Islam reportedly forbade the painting of human beings (including that of Prophet Muhammad) as many Muslims believe that pictorial representation of the human form may tempt followers to commit idolatry.

Though the Qur’an itself does not prohibit pictorial representation, commentaries on it do. Muhammad’s follower, Ibn Umar, reported him as having said, “Those who paint pictures will be punished on the Day of Resurrection.” “Later Islamic scholarship,” says Saeed, “doubtlessly following interpretations of these hadith, suggested that if artists represented living beings such as people or animals in their work, it would infringe on the creative agency of God.

“On the other hand, those who argue that there is no absolute prohibition stress the difference between making idols for religious worship and constructing images for entertainment. They say that ‘anti-representation’ confuses categories and intention, which had led to a polarization of the debate. One argument is that if images were used in the presence of the Prophet without his objection, there can be no reason why they should be considered universally prohibited.”

Pattern as Cosmology in Geometric Islamic Art: 4

Appendix

Condensed and edited quotations from Oleg Grabar, The Formation of Islamic Art (New Haven: Yale U. P., 1973, rpt. 1987)

(1) Let us sum up the historical evidence [concerning] the Muslim attitude toward the arts and suggest an explanation for it. . . . The Arabian cradle of Islam was only dimly aware of the possibilities of man-made, visually perceptible, symbols; it was not creative itself but [rather] ‘consumed’ objects. It knew that other cultures . . . did erect fancy buildings, paint pictures, fashion sculptures, and even gave a certain sacredness to these creations. But their meanings . . . were either primitive or limited, and more general aesthetic impulses other than those of owning a ‘pretty’ thing, were absent. They were absent from the Koran and the Prophet’s message, with its emphasis on a unique God forcefully distinct from the Christian . . . . During the first century after the conquest the Muslims were brought into immediate contact with the fantastic artistic wealth of the Mediterranean and [of] Iran. They were strongly affected by a world in which images, buildings and objects were expressions of social standing, religion, political allegiance and intellectual or theological positions. . . . [T]he Christian world was . . . proud of both its sophistication in the use of the visual and its technical mastery of the beautiful. . . . In view of the wealth of religious imagery and luxury objects identified in Central Asia, the same . . . development may be suggested east of Byzantium. That the Muslims were impressed by the artistic complexity of the conquered world goes without saying. To use the term introduced by Gustav von Grunebaum, they were clearly ‘tempted,’ and we can document the accumulation of wealth together with new habits of luxurious living and the search for visual symbols of their own, including representations of personages and things.”

(2) “But then the search stopped, or rather in the official art of mosques and coins a substitution occurred from older themes with a constant use of living things into writing or into conscious modifications of the models used. These substitutions still had iconographic content, but they lacked one element, which tended to be de rigeuer in earlier or contemporary traditions, that is, representations of living things. Even though notable exceptions exist, this avoidance of, or reluctance toward, representations spread beyond the realm of official into private art. By the end of the eighth century Muslim thinkers were asking themselves why they made this shift, and they answered by going back to incidental passages [in] the Koran and by reinterpreting the life of the Prophet. Why, historically speaking, did this change from indifference to opposition take place? It has generally been assumed, quite correctly, it seems to me, that the doctrine (or at least the elements thereof) of opposition to representations followed rather than preceded the actual, partial, abandonment of such representations. It is therefore not through the impact of a specifically Muslim thought that we may provide an explanation. Some have argued for a basic Semitic opposition to images that would have come to the fore with the formation of the Arab empire. Besides being ethnically focused, this explanation is weakened by the existence of an art sponsored by Semitic entities since Akkadian times. Others have argued for the immediate impact of Judaism, and it is true that converted Jews played a very important part in the formation of early Islamic thought. Furthermore, a number of events with iconoclastic overtones, such as the edict of Yazid, were said to have been inspired by Jews.”

(3) “Judaic arguments may have played an important part in the formation of a doctrine against images, but it seems improbable to me that they would have triggered it, mainly because doctrines about the arts always occur first as a reflection [regarding] the presence of a work of art, not as an intellectual position. Then, in the one instance, coins, where images were formally abandoned, there is no evidence for a Jewish influence, nor is one likely. It is simpler to argue that the formation of a Muslim attitude toward the arts was the result neither of a doctrine nor of a precise intellectual or religious influence. It was rather the result of the impact on the Arabs of the prevalent arts. Or, to put it another way, Islam burst onto the stage at the moment . . . when images became more closely related to their prototypes rather than to their beholder, when religious and political factions fought with each other through images, when Christology of the most complex kind penetrated into the public symbols of coins. The new Islam could choose to compete in this particular world, and it did try, in some coins, to develop a symbolic system of its own. The difficulty was, however, not only that the Christian world in particular had acquired a tremendous sophistication in the use of forms, but also that in order to be meaningful an identifying symbolic system of visual forms has to be known and accepted by all those for whom it is destined. If it used, even with modifications, the terms of the older and more developed culture, Islam would lose its unique quality. On the other hand, the visual weakness of its Arabian past did not provide Arab Islam with the visual forms that could be understood by others or with the technical sophistication needed to manipulate existing forms.”

(4) “The reform of Abd al-Malik crystallized an attitude that had developed in the Muslim community, according to which the use of representations tended to idolatry; no understandable visual system other than that of writing and of inanimate objects could avoid being confused with the alien world of Christians (and, eventually, of Buddhists or pagans). It was therefore . . . the ideological and political circumstances of the late seventh-century Christian world that led Islam to this point of view. For it is in a complex relationship to the Byzantine Empire that early Islam tried to define itself. This point appears clearly in many of the accounts that describe Abd al Malik’s coinage or the bringing of workers from Constantinople to make mosaics in Damascus. Most accounts describe these two events as, respectively, a challenge to the Byzantine emperor and his subjection to the caliph. Actual historical truth here is less important than the mood that it suggested. To conclude, then, we might say that, under the impact of the Christian world, Islam sought official visual symbols of itself but could not develop representational ones due to the nature of images in the contemporary world. Precise historical circumstances, not ideology or a mystical ethnic character, led to this attitude. One corollary is that we can define a Muslim attitude toward the arts only in the one limited area of the representation of living things. There was no definable attitude toward other aspects of the arts. One can simply assume the maintenance and taking over by Islam of prevailing attitudes in the conquered world. The other corollary is that a defining attitude appears in culture only when it fears that the prevalent attitude is dangerous for the culture’s unity and cohesion.”

(5) “The question is this: If the Islamic reluctance to [produce] images was the result of specific historical circumstances, why did it remain after the removal of the circumstances, during the Iconoclastic crisis in the Christian world and after the Islamic empire had become fully established? For an answer, we must turn to the philosophical or anthropological, aspects of our problem. The attitude of early Islam is more than simply the result of concrete historical circumstances; it is typologically definable and understands a representation as somehow identical with that which it represents. This attitude has been a constant in the history of the arts, at times in the forefront as in much of ancient Egyptian art, at other times muted under the impact of some other aesthetic or social impulse, as in classical Greek art. . . . The peculiarity of the Muslim attitude is that it immediately interpreted this potential magical power of images as a deception, as an evil. This iconophobia has several further aspects. In itself it was not a rejection of symbolic content in the Damascus mosaics or in the use of writing on coins. But the later history of the Damascus mosaics is instructive, in that they, like the slightly earlier Dome of the Rock mosaics, lost their symbolic, or at least traditional, meanings very rapidly. Only through incidental remarks is one able to reconstruct their original meanings, and even then some doubts and uncertainty surround these interpretations. Matters are different when we turn to writing, which remained as the main vehicle for symbolic signification in early Islamic art. The point at this stage is that the rejection of a certain kind of imagery due to its deceptive threat carried with it considerable uncertainty about the value of visual symbols altogether.”